In the twilight years of the Russian Empire, as the Romanov dynasty teetered on the brink of collapse, two princesses from Montenegro - Milica and Anastasia - wove a web of intrigue, mysticism, and influence that ensnared the highest echelons of Russian society. Their fascination with the occult, coupled with their close relationship with Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, forever altered the course of Russian history. But who were these mysterious women, and how did they become such influential figures in one of history’s most dramatic downfalls?

Crows and Cockroaches

Born to King Nikola I of Montenegro and Queen Milena, Princess Milica and her younger sister, Princess Anastasia, were raised in an environment that valued education, ambition, and strategic marriages. Their father, a shrewd ruler, ensured his daughters received a comprehensive education, preparing them for influential roles on the European stage. Both sisters were then invited by Tsar Alexander III to be educated at the prestigious Smolny Institute of Noble Maidens in St Petersburg, cementing their ties to the Russian aristocracy.

It’s a sign of how well regarded Milica was in the Russian court that Tsar Alexander III himself proposed to her on behalf of his nephew, Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich. The marriage was described as the greatest victory of the Montenegrin people without a battle and spilled blood. Anastasia married Prince George Maximilianovich of Leuchtenberg but the pair divorced after 13 years. The divorce was considered controversial at the time as they had children and people at court even questioned why it was granted. Rumours abounded that Anastasia had left her husband for the most handsome man in Russia: Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich.

The rumours were true. Anastasia and Grand Duke Nicholas married in 1907. Nicholas was a strikingly tall war hero - an attractive match for any woman at court - but he was also Peter Nikolaevich’s brother and Russian Orthodox rules meant that sisters were forbidden to marry brothers. It was already bad enough that these two foreign women had snagged two of the most eligible men in Russia. In fact, Milica and Anastasia were two of only three foreign women to marry into the Russian imperial family (and the third was their niece). But it was clear that the Romanovs favoured the sisters and were bending the rules to suit them.

Milica and Anastasia were described as intelligent and well-educated but their strong personalities and air of superiority already got peoples’ backs up, even before such an obvious display of favouritism. The Russian aristocracy, always wary of outsiders, resented their influence within the Russian imperial family. The sisters were often sneeringly referred to as “The Black Peril", “The Crows” and “The Cockroaches” - a nod to their dark hair, foreign origins, and, most notably, their unshakable belief in the occult.

The allure of the occult

Unlike most noblewomen at the Russian court, Milica and Anastasia were not content with hosting grand balls, drinking tea, or engaging in idle gossip. Instead, they immersed themselves in the world of mysticism, alchemy, and spiritualism. They studied ancient texts, participated in seances, and surrounded themselves with an eclectic mix of astrologers, clairvoyants, and self-proclaimed magicians. Their knowledge was not purely superficial. Both sisters received honorary doctorates in alchemy from Paris, demonstrating their serious commitment to the esoteric arts.

The sisters’ fascination with the supernatural was more than just a personal hobby; it became a way for them to wield influence at the Russian court. At a time when mysticism and spiritualism were fashionable among the European aristocracy, the sisters cleverly positioned themselves as intermediaries between the supernatural and the imperial family. This was especially true with Empress Alexandra, who was devoutly religious and desperately seeking answers in a world that seemed increasingly hostile to the Romanovs.

Gaining the trust of the Empress

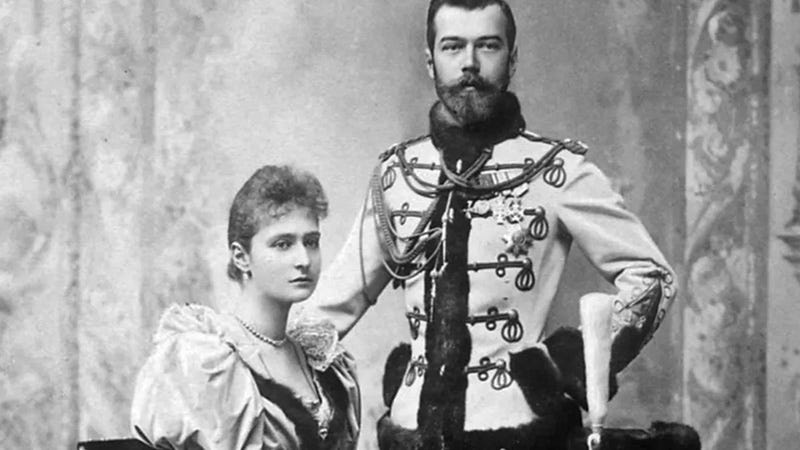

Empress Alexandra was unpopular in Russia. She was a quiet, humourless woman who couldn’t speak Russian, so it was hard for her to make friends. Her shyness was often mistaken for arrogance, especially as she refused to host the grand balls and other social events expected of her. What’s more, she struggled to produce a male heir and suffered a number of miscarriages. Her fertility problems became common knowledge at court and people would spitefully gossip about them. When she finally gave birth to a much-needed son, he inherited the haemophilia that blighted Alexandra’s family.

Alexandra was lonely and vulnerable, which is where Milica and Anastasia stepped in. Despite her Lutheran upbringing, Alexandra had always been drawn to mysticism and spirituality. Burdened by her inability to produce a healthy male heir and plagued by anxiety, she was willing to embrace any avenue that promised divine intervention.

Milica and Anastasia introduced the Empress to a series of mystics and healers, each claiming to possess extraordinary powers. The most famous of these early encounters was with French occultist Nizier Anthelme Philippe, known as Monsieur Philippe. A former butcher’s assistant turned mystic, Philippe claimed to have the power to heal the sick, communicate with spirits, and predict or even change the sex of unborn children via “magnetic powers”. The Empress, desperate for a son, was impressed by his abilities and granted him unprecedented access to the royal family, against the advice of in-laws who could see the mistake she was making.

Philippe’s influence over the Empress caused immediate controversy at court, with many members of the Russian aristocracy alarmed by the growing reliance on a foreign mystic. His time in Russia was short-lived. When he failed to prevent another miscarriage, a humiliated Alexandra sent him back to France. However, his final prediction - that a long dead saint would grant Alexandra a son - came true. Shortly after bathing in the waters of a sacred spring associated with this saint, Alexandra became pregnant with her son. After this “confirmation” of a divine intervention, she came to rely even more on Milica and Anastasia.

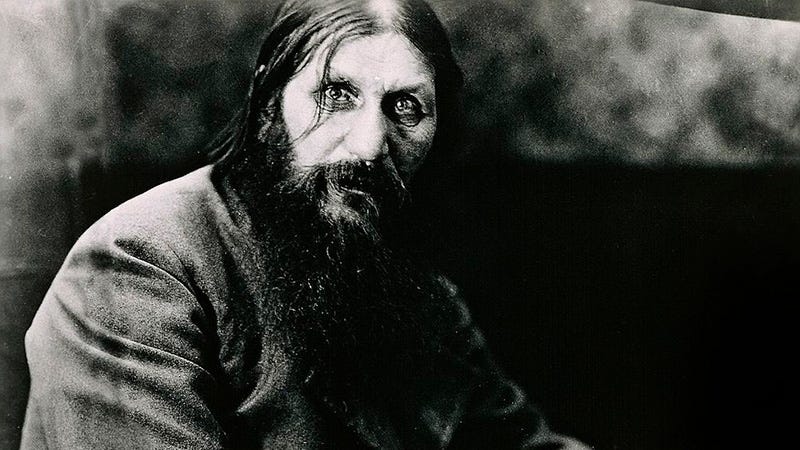

But Monsieur Philippe’s departure left a void, one that would soon be filled by an even more enigmatic and controversial figure: Grigori Rasputin.

The rise of Rasputin

When Monsieur Philippe failed to deliver the healthy son the Empress desired, the Montenegrin sisters set out to find a new mystic to retain their influence. Their search led them to Grigori Rasputin, a Siberian peasant and self-proclaimed holy man with a growing reputation as a miracle worker. In 1905, Milica introduced Rasputin to the imperial family, an event that would alter Russian history forever.

Rasputin’s effect on the Tsar and Empress was immediate and profound. His hypnotic presence and apparent ability to alleviate the suffering of Tsarevich Alexei convinced Alexandra that he was a man of God. As his influence over the royal family grew, so did tensions at court. Many members of the aristocracy viewed Rasputin as a charlatan and a threat to the stability of the empire. Yet, the Empress remained fiercely loyal to him, convinced that his presence was essential to her son’s survival.

Ironically, Milica and Anastasia had, in their pursuit of influence, sealed their own fates. Once the gatekeepers to the Romanovs, they now found themselves sidelined as Rasputin became the Empress’s closest confidant. Their own status diminished, and they watched in frustration as their former protégé became one of the most powerful people in the Russian court.

From power brokers to outcasts

As Rasputin’s influence grew, so did the scandals surrounding him. His debauchery, erratic behaviour, and rumoured affairs with noblewomen and prostitutes alike became the talk of St. Petersburg. The aristocracy, already resentful of his presence, began to conspire against him. In December 1916, a group of nobles, led by Prince Felix Yusupov, assassinated Rasputin in a crazy plot that involved poisoning, shooting, and drowning.

By this point, Milica and Anastasia had already faded from the political stage. The Russian aristocracy had turned against them, seeing them as the original architects of Rasputin’s rise. Grand Duke Nicholas had made his feelings about Rasputin clear and demanded his wife make a choice. Sensibly, Anastasia sided with her husband. When the Russian Revolution erupted in 1917, both sisters knew their time in Russia was over.

Anticipating the violent turn of events, both Milica and Anastasia fled Russia before the full-scale collapse of the monarchy. Milica and her husband eventually settled in Italy, where they lived under the protection of her sister, Queen Elena of Italy. After the abolition of the Italian monarchy in 1947, Milica relocated to Alexandria, Egypt, where she remained until her death in 1951. Anastasia’s later years were similarly spent in exile, far removed from the court where they had once wielded considerable power.

If you’d like to support my work but can’t commit to a regular paid subscription, you’re welcome to leave a small tip on my Ko-fi page.

Milica participated in the end of three monarchies? Not saying it’s her fault, but not saying it isn’t…

This is heavy! They set the fire and got out fine. And the Romanov died. Not fair.